Design credit: Václav Pinkava

It is my great honour to introduce translator Melvyn Clarke on Angels and Lions. Melvyn is one of the few people to have mastered the Czech language to the point of translating novels into English. His translations include the ever-popular Hrdý Budžes, while the sequel, Onegin Was a Rusky, was published at the end of April.

In this post Melvyn talks about Czechlist, a FB group in which Czech and English language professionals meet to discuss language problems. The group has been invaluable to my professional development and is the first go-to site if my students ask any odd questions.

This post is also about using translation in an ELT class and provides some hands-on activities teachers can use. I am very excited about this, because translation is something of a neglected area in the English classroom, yet it is part of many students’ lives at their workplace, and a fantastic learning resource.

Over to Melvyn:

For language professionals and enthusiasts in the Czech Republic, Czechlist will surely need little introduction. Ever since 1999 we have been discussing Czech<>English language issues (details here), and building up a substantial archive of interesting comparative material, along with a collection of online language resources and a set of articles on classic Czech>English translation issues .

Discussions often take the form of cosy fireside chats :-), with issues viewed from multiple angles, rather than polarized polemics (though these too have their occasional place). This is an important point, because Facebook arguments have long been considered notorious for their adolescent troll-fest nature, but we have generally moved away from such diatribes and invective (except perhaps on Saturday nights :-O ), towards a more polyphonic dimension. 🙂

A random glance at any thread in our archive will most likely reveal a collegial discussion that is informal and relaxed, but more often than not with a serious point and purpose buried beneath its various odd tangents (and even those tangents can have a serious role to play, as we shall presently see). So despite the often light-hearted tone, Czechlist does serve a serious purpose for all those working in the translatosphere.

While originally I set it up back in 1999 primarily for translators and interpreters, we have been joined over the years by many other language professionals and enthusiasts with an interest in discussing translation issues, e.g. translation agency staff, editors, students, people from all walks of life with bilingual superpowers, 🙂 and in particular language teachers.

Now how can a discussion group like this be of use to language teachers and other language professionals?

Teachers translating – translators educating…

Well, do we translators spend our online lives huddling in ivory-tower private groups, grumbling righteously amongst ourselves about non-translators? Of course not. We are active within the community, helping out with individual language issues (which is not to say we normally work on texts for free, of course). Discussions between translators and teachers are particularly fruitful. A substantial proportion of the issues we deal with emerge not just from our everyday work and practice, but also from the classroom… and sometimes from the translation classroom.

Now translation in the classroom has, alas, long been looked down upon as a Cinderella subject within TESL, overshadowed by communicative methodology, but in my experience students find it a useful practical skill that is increasingly required in the working world. Even back in 1989, Alan Duff’s seminal work on the subject (Translation) points out that in the wider working world, translation is a natural and necessary communicative activity, “hence it is legitimate to reinstate it in the language classroom”. He asserts (as pointed out by Peter Newmark) that translation develops three qualities essential to all language learning: accuracy, clarity, and flexibility. “It trains the reader to search (flexibility) for the most appropriate words (accuracy) to convey what is meant (clarity)”. Importantly, Newmark points out that translation exercises in themselves facilitate language learning. Duff says: ‘’teachers and students now use translation to learn, rather than learning translation.’’

More recently, Sara Laviosa’s Translation and Language Education: Pedagogic Approaches Explored has highlighted the importance of teaching the connotative and illocutionary dimensions in the translation process, while Multiple Voices in the Translation Classroom by Maria Gonzalez Davies details some of the structured activities that can be used in the translation classroom and workshop to spotlight the holistic approaches required by the translation process over and above mere dictionary equivalents, e.g. considerations of the various translation approaches needed for various end-users and the pitfalls of different genre and register traditions in various cultures.

Activities discussed include: analysing mistranslations found in the mass media, menus, literary translations and public signs; analysing registers, communicative purposes (skopos theory) and genres by comparing synonyms; analysing naturalizing strategies and exoticizing strategies (AKA domestication vs. foreignization); transferring cultural references (“Anything else, luv?” at the market, or “I think I’ll go to ‘Boots’ for aspirins”); back-translations; translating jokes (‘’The translation fails if the spectators do not laugh’’ — Newmark); deducing an original literary text from two different translations of it; and gapped translations.

The latter is one of my favourite activities in my Belisha Beacon translation workshops. Students are presented with an original text and a parallel L2 translation with interesting words and phrases clozed out. This gives rise to various suggestions for discussion, some disputably ‘better than the original’, though an important conclusion to be drawn is that everything depends on the requirements of the end user, so if no background is given to the text (not always a good idea!) then there can often be no single ideal translation, a point normally missed in classic ‘la plume de ma tante’ language textbook translations.

Corpus activities can also work in a similar way. Some mature students harking back to the halcyon schooldays that they are perhaps hoping to reenact 😉 can have a rude awakening when they find dictionary standards are so little adhered to in practice.

Another favourite task of mine was inspired by the old Institute of Linguists Diploma exam: annotated translations. Here students are invited to identify x number of awkward translation problems within a text and to provide notes on the nature of the issue and their method for arriving at a solution, i.e. to focus on their translation process rather than the translation product). These “thinking aloud” notes can then be discussed in the group.

More classroom translation activities and project work here and here.

The lesson does not end when the bell rings. Quite the reverse, students are encouraged to take part in Czechlist discussions and flame wars, 🙂 which with any luck will then spill over into the next lesson.

Mention should also be made at this point of some very interesting extramural translation projects run by a Czechlist colleague at the University of Sheffield’s Czech Department . The Translating Czech Castles project is particularly inspiring.

Dubbing projects may also play a useful educational role.

In a world where machine translation often clouds communication, and where to some extent ‘everybody’ is now a translator for fifteen seconds, the importance of this holistic, sensitized approach to translation surely becomes increasingly important, and should be stressed more in both the state school and the adult education classroom.

In this respect an online forum like Czechlist can help a lot IMO, complementing one-to-one dictionary equivalents with a web of alternatives, synonyms, connotations, componential analysis and ‘’what we might say in the same situation’’. In this light all those tangents suddenly do not seem quite so tangential. According to Aleš Klégr in his book The Noun in Translation, only 70% of Czech nouns in published literary translations are translated by dictionary equivalents (and his subsequent research has shown similar results for other parts of speech). Hence we find the dictionaries are fine as far as they go, but to bring your Czech/Slovak<>English translations to life you need other resources, not least of which is Czechlist and the Czechlisters, who I cannot stress enough are a tremendous bunch of professionals. 😉 We can provide the right word instead of an ‘almost right word’, which as Mark Twain once said, is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug. Nor should we forget that there are many other excellent language discussion groups of a similar kind out there.

Translation theory, alas, sometimes obscures more than it clarifies (as Peter Newmark frequently pointed out), because its practitioners often seem too mesmerized by their own abstruse terminology and abstract wheels within wheels to be able to helpfully present specific examples in clear contexts, and yet the simple, everyday yet eternal translation task of finding the right delicate semantic balance within each momentary context is one that can be grasped immediately even by (or especially by?) schoolchildren, as I have seen in an initiative like Budžes jde do světa, where we discuss the nuts and bolts of literary translation with some very receptive grammar school pupils.

Discussions on Czechlist do not only deal with lexical issues. With the many marvellous linguists, literary translators and language buffs active in the group we are increasingly involved in more wide-ranging translation and language issues, e.g. here and here. Translation theory book reviews can also be found.

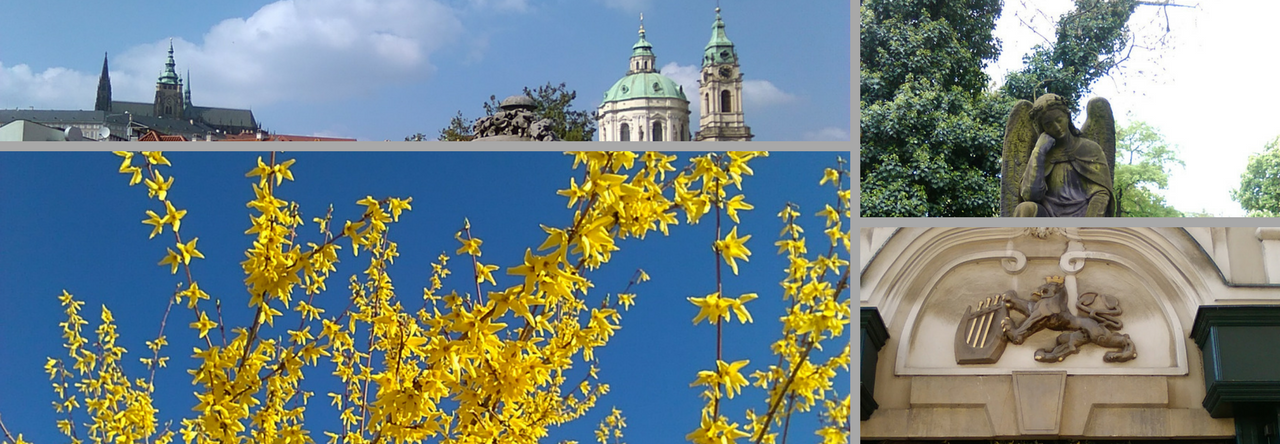

Nor should we neglect the social activities that have been a regular Czechlist feature ever since its creation. Any Czechlister can suggest a Czechlist gathering anywhere, so every few weeks Czechlisters get together at Prague or Brno cafes, tea houses or pubs for more or less informal gatherings, where we normally raise various translation and teaching issues. Some Belisha Beacon workshop attendees have been regulars at these meetings.

Do you have any interesting Czech-English language issues to bring up on Czechlist…not only lexical problems, but perhaps grammar or more general issues? We are all ears… It would also be interesting to hear about similar discussion groups for other language combinations, or you might want to suggest some other translation-related exercises. Any other comments also appreciated.

Pingback: Office English 7 – Contracts – Kamila of Prague

Great experience and trend that brings together teachers and translators

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: How Learning A Second Language Can Help You Teach EFL

Pingback: How Learning A Second Language Can Help You Teach EFL | Fluentize

Pingback: How Learning a Second Language Can Help You Teach English - BridgeTEFL

Pingback: Osm poznámek k výuce pádů v češtině pro cizince – Kamila of Prague